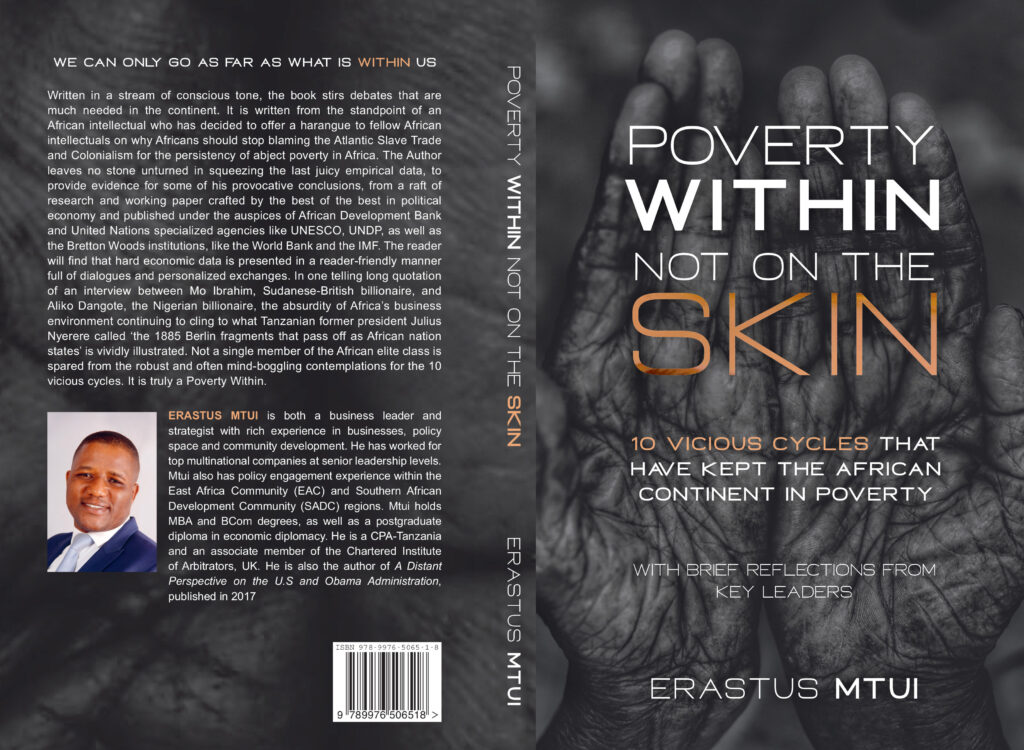

Dialogue with Erastus Mtui, author of Poverty Within Not on the Skin. 10 Vicious Cycles That Have Kept the African Continent in Poverty, Dar es Salaam, 2021. [LINK TO ITALIAN VERSION]

I met Erastus Mtui, a Tanzanian economist, business leader and strategist, about two years ago during one of my first visits to East Africa. We met at the university of Dar es Salaam, and he brought me his book as a gift. I confess that at first, amid my naïve enthusiasm for Africa, I skimmed through it with some skepticism because it seemed to me to be re-proposing a developmentalist analysis of Africa that I rejected outright at the time. As usual when it comes to sub-Saharan Africa, I was wrong. For two reasons: the first is that the book, printed in 2021, is an invaluable source of information and data often ignored by Western media. The second is that Erastus’ unsparingly and passionate critique comes from within, that is, from those who live and work there, struggling every day to improve their country and region. Two years later, I had to admit that in many things Erastus was right. That does not mean I fully embrace his analysis, as in my opinion it remains within the framework of Western political-economic thought, suggesting an “African way” to capitalist development. Both because of this and because of my scholarly interests and research background (sociology of communication and culture), I preferred to focus our dialogue on two aspects that also relate to my personal experience: the general issue of education (chapter 2) and the cultural issue of the so-called “self-defeating” mentality (chapter 5) – which often translates into practical and existential self-boycott.

Erastus, before starting, would you please tell us very briefly about your current intellectual and business activities? What are you up to in these days?

I have proceeded to become a public servant, working as Tax Ombudsman for Tanzania. This is an important role that contributes to resolve tax complaints which in the end would contribute to increase in voluntary tax payment and building better business and investment environment in the country. It is an honour to be appointed in this role.

I have to confess that after almost three years of African life, I have started to understand better and therefore appreciate even more your book. But what in particular motivated you to write it?

Africa has a unique reality coupled with lot’s of issues that need conscious efforts to resolve. However, many of us, have chosen to blame ‘others’ for the many problems and issues we face; sometimes blaming everyone else except us. While I understand and appreciate there has been a lot of external factors influencing the current realities in the continent, there is a lot more within us that contribute not only to the issues, but in some cases go beyond to impeding resolution of the problems. The book intends to invoke the significant role we play as Africans in creating and or perpetuating many of the issues we have. It aimed to challenge each one of us-from leaders to a common person, communities to nations to be masters of our own destiny. This could only happen if we address most critical factors within us.

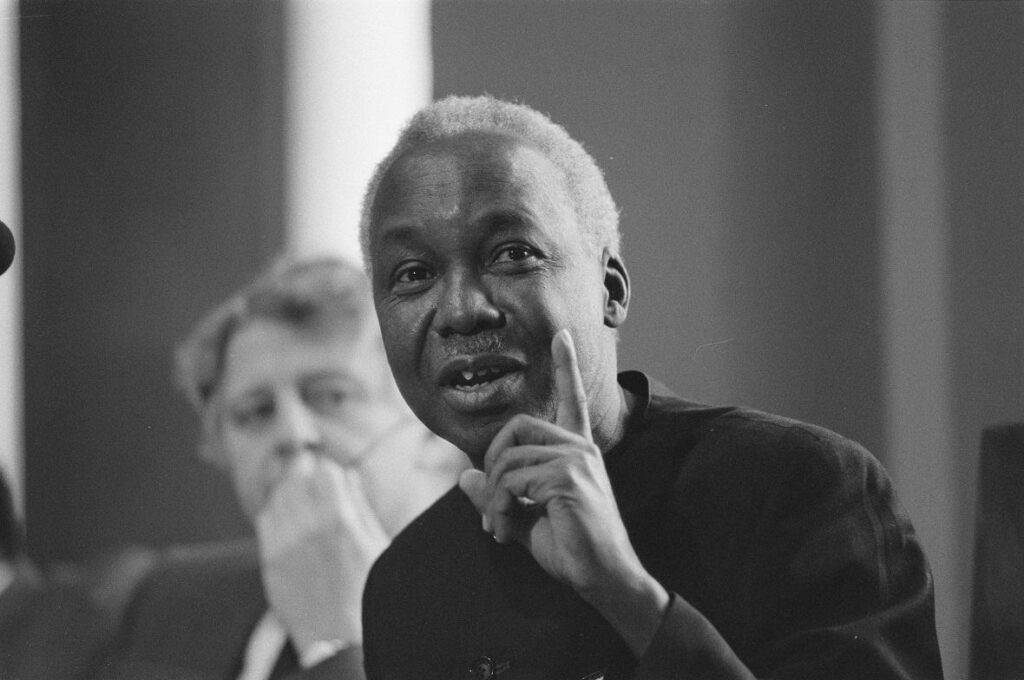

Although the whole book would deserve to be discussed at length, for reasons of space I would like to focus our dialogue here mainly on two aspects (or “vicious cycles”, as you call them) that attracted my attention as a scholar and educator: poor education systems (chapter 2) and self-defeating practices (chapter 5). Regarding the first point, among other things in your book you report data from the World Bank according to which in 2019 (and current data do not differ much: the global average enrolment in tertiary education institutions was around 39 percent, while sub-Saharan Africa is stuck at around 9 percent. Later you emphasize that it is not just a matter of multiplying the number of universities and enrolments, but rather focusing on specific types of education, and you give the example of China, which for approximately 20 years converted more than 600 general universities into polytechnics. I understand the value of your proposals, but I would like to ask a question that goes a little deeper and is also the result of my observation as a teacher here in Tanzania. If it is true, as you write, that there can be no economic development without educational and cultural development, doesn’t it seem to you that the key issue is to work on enhancing the concept of culture itself? What I have noticed, and not only in Africa, but also in Europe, is that more and more education is considered just another commodity with a price label on it, not a process of shaping the individual and nurture our minds. What kind of socio-economic development can we expect if education of all grades is de-linked from its potential to develop and – as Nyerere would have put it – liberate the individual?

It is breath-taking to deep dive into the statistics for education in Africa. They are not favourable by any standard. Should we be ashamed to mention these realities, I believe not. To the contrary, accepting and dialoguing on these facts would be a good step to finding lasting solution. In answering your question, I would start by picking on the last part of your question…. “as Nyerere would have put it-‘liberate’ the individual’”. Our education needs to liberate us, starting from individual himself/herself to our community and nations. The example you have given from the book that shows that China converted 600 general universities to polytechnics is a good example of evaluation and question that China I believe responded to: “is our education helping/working for us?” Like it is well put in the book, many African countries took a different direction, converting polytechnics to universities. There are a number of things that needs to improve in many of our African educational systems. When Sub Saharan Africa’s average tertiary education enrolment is at 9 percent while the world average is at 39 percent, then a significant transformation is needed to catch up-just on numbers. The second improvement needed is quality of the 9 percent. Given the obvious environment well discussed in the book, quality of the enrolled 9 percent needs focus and huge improvement. Possibly the third layer would then be your last part of the question, how best does that education serve the purpose of these individuals and communities. You can have quantity and quality which do not serve the purpose. In the scenarios discussed in the book, all three elements need significant transformation. If we had to move the world (doing all we can), to change Africa, then investment in education, in form, quality and purpose would be central pillar to that discussion. My own country has recently come up with highly improved new education policy which focuses on skills, giving impetus and emphasis to polytechnics among other improvements. This is one of the ways to go!

On the subject of the freedom and universality of the educational system, in a book collecting the writings on education of the father of the nation, Julius Nyerere (himself a teacher, I remind my readers), we read: “the very blow against equity in education and the principle of ‘education for all’ was the imposition of school fees, i.e. cost sharing, which was one of the conditions for World Bank loans in the early structural adjustment days”. These demands are reiterated by every international financial body at any latitude (see what happened with Greece in EU in 2010). The message has been systematically this: “if you want the money you need to cut the welfare: public education, health and welfare”. But how can such measures be invoked in the name of “development”? And in your opinion, in the current economic-financial circumstances, is it possible for African countries to invest in public education, or do the conditions set by the big financial institutions still make it an impractical goal?

I would say it is a mixed bag! While it is absolutely the right thing to fund public education-which many African countries have attempted; the size of economies, revenue collections versus competing dire needs of so many and so much have somehow hindered such moves thereby affecting both quantity and quality of education. That said, when faced with multiple needs, it is the choice we make that will set us free. I believe as Africans we have opportunity to choose to focus on education and give it our best for sustainable emancipation and development. As I wrote in the book, there is no community or nation that has developed beyond its education levels. Again, I would not get into the trap of blaming development partners, the responsibility is squarely ours to decide.

One of the most important aspects of your book, in my opinion, is the unapologetic self-criticism to certain aspects of African culture. I confess that in reading Chapter 5, where you list and discuss “self defeating” attitudes and behaviours, I recalled my own experience over the past three years: a chronic inferiority complex towards all things foreign, the associated poor quality of goods and labour, the lack of cooperation among Africans (if not open hostility), the tendency to think as “ a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”, the lack of responsibility towards the work environment, etc. You argue that for these and other self-defeating attitudes Africans cannot blame colonialism or the International Monetary Fund… but start to identify and deal with their own responsibilities. The whole thing could be summed up, perhaps, with a story you tell the end of the chapter: “I cannot recall a friend who has never lost money and never had to terminate a business venture. How can we nurture our ubuntu in such an environment?” The reference to ubuntu, a key concept in African culture and philosophy, struck me, because often in the West we tend either despise or idealize Africa, and ubuntu belongs to the latter attitude. However, as you recall in previous pages, ubuntu (roughly: “community”) derives from the phrase “Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu” in the Nguni language of Xhosa, Zulu, or Ndebele. The phrase can be translated to mean “A person is a person through other persons,” or “I am because we are.” My first question concerns this aspect, because I sense a potential friction in your argument: how would you reconcile the attitude of entrepreneurial competitiveness, private initiative and, in short, the “spirit of individualism” that permeates your book, with a philosophy that is anchored in cooperation, participation and collective sharing? It is no accident that many African socialist leaders, such as Nelson Mandela, were inspired by the ubuntu philosophy. Don’t you think there is a potential conflict between European bourgeois, capitalist, imperialist culture and African cultures that identify themselves with ubuntu? And finally, what do you think survives in Africa and Tanzania today of concepts and practices like ubuntu or ujamaa (Julius Nyerere’s political philosophy)?

There is so much that needs to be addressed regarding these “self-defeating” behaviours. It is truly breathtaking to consider how these behaviours and attitudes intersect with the other factors discussed in the various chapters of this book. On the other hand, I don’t believe there is any conflict between the concept of Ubuntu and the attitudes, behaviours, and values indirectly proposed in the book. In fact, if the attitudes and behaviours discussed in Chapter 5 were addressed or changed, they would strengthen Ubuntu. “I am because we are” would, in turn, foster more trust, more collaborative businesses, and more joint ventures, not less. I would argue that Ubuntu needs to be cherished and nurtured, but the attitudes, behaviours, and tendencies highlighted in Chapter 5 urgently need attention—and needed now.

The last reflection I would like to share with you goes off the track indicated at the beginning, of this dialogue, but I think it would be useful to grasp the dimensions of the African challenge. So let’s move on to the seventh chapter: ‘Overdependence on Nature’. Here on the one hand, you criticise the continent’s tendency to self-celebrate its natural resources (but then not knowing how to exploit them), but on the other hand you explain how Africa, with 60% of its arable land, contributes only 4% to world agricultural production, despite having 70% of its labour force concentrated in the agricultural sector. Even more surprising is that, according to the FAO, Africa spends about 33 billion dollars a year on importing four products: wheat, maize, rice and palm oil. As you highlight, North Africa alone imports 15 million tonnes of maize per year worth $3.5 billion: the equivalent of the value of all tea and coffee exported annually from the continent. Now, the answer you seem to be offering to these undeniable challenges, from what I understand, would be that of increasing industrialisation and technologisation (your admiration in this field for Israel is revealing). For some years now, I have been following the debate on the so-called ‘green revolution’ in India, a process of industrialisation of agriculture, strongly sponsored by the United States, which has ended up producing more harm than good, especially to small and medium-sized local communities. You may remember the protests of Indian farmers who took to the streets in their millions across the country at the height of the pandemic to protest against Modi’s proposed reforms, which would have essentially damaged the majority of smallholders. As The Scientific American wrote: “the farm laws intrude upon the regulatory powers of state governments and intensify the already severe power asymmetry between corporate houses and the mass of Indian farmers, nearly 86 percent of whom cultivate less than two hectares”. Sorry for this lengthy preamble! My question is: do you think it is possible to balance agricultural industrialisation with the self-sufficiency of the small and medium-sized farmers who make up the main fabric of the continent food production? And are we sure that for most of Africa, technological innovation would be compatible with food and environmental sustainability? Some independent research warn us against the digital platformization of the food production chain.

One thing I would propose here is adopting a problem-solving mindset. The world has always had no shortage of alternative solutions. Let me highlight four key points:

– There is a vast, untapped opportunity in Africa’s agriculture. Despite the continent holding 60% of the world’s arable land, it contributes only 4% to global agricultural production. This disparity cannot be justified by any standard.

– Africa is uniquely positioned to feed the world with better-cultivated, natural food that could command premium prices—especially if it decides to mass-produce using its own distinct methods.

– Technological advancements and the application of best practices are essential to achieve the significant improvements needed in agriculture.

– The choice of technology is crucial to ensure environmental sustainability. With a problem-solving mindset, Africa has the potential to innovate new, unique approaches to improving its agriculture, hoping to use some of the already available good technologies – assuming that not all available technologies are harmful.

– Africa is uniquely positioned to feed the world with better-cultivated, natural food that could command premium prices—especially if it decides to mass-produce using its own distinct methods.

In other words, Africa remains the last major player with relatively easier choices to make. I don’t feel I’ve fully answered your question without mentioning the critical importance of adding value to agricultural products. Take the case of Ghana and Ivory Coast cocoa—together they supply 60% of the world’s cocoa beans, valued at USD 7.5 billion annually. Meanwhile, the value of the chocolate market exceeds USD 100 billion each year. By any standards, something needs to be done. While there are certainly practices that need to be addressed, improving agriculture and the related value chain is one of the most vital areas for development in Africa.